DEATH AT GOVETTS LEAP

By Bella Greaves

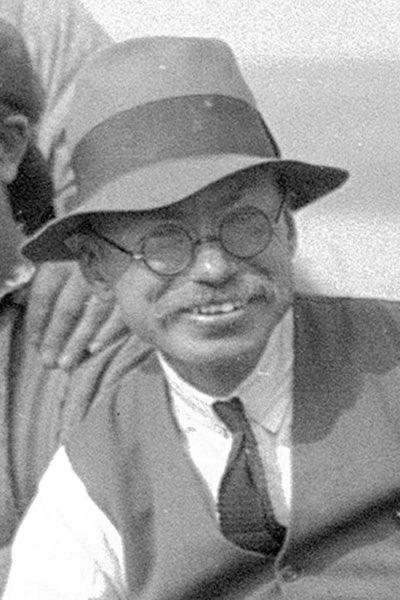

We know quite a bit about the tragic end of Vere Gordon Childe, a prehistorian who killed himself near Govetts Leap in 1957. Childe had a massive reputation among both academics and the general public – many of his books on the early development of human societies had been bestsellers. In fact, in terms of international fame during his lifetime, he remains the best-known Australian writer of all time.

Childe spent most of his adult life in London, where he was a professor, but retired at the age of sixty-five and returned to Australia for a visit. A single man with no children, he could do whatever he liked with his time now. In the next few months he visited the Blue Mountains, which he loved, examining their geology. He’d spent a lot of his childhood here, with his parents in their holiday house at Wentworth Falls.

At 7.40am on Saturday 19 October, Childe emerged from the Carrington Hotel in Katoomba, where he was staying, and took a taxi from the rank outside. He asked to be driven to Govetts Leap, and didn’t say much during the journey, concentrating on his pipe. Arriving at the look out, he asked the driver to wait a few hours, as was his custom on these trips to various local spots, and headed off along the cliff top track in the direction of Bridal Veil Falls. He was wearing a brown felt hat and a blue-green sports coat, and equipped with a pen and paper and a compass.

The driver assumed Childe would return in time to be taken back to the Carrington for lunch, but by midday there was no sign of him. Then some people came down the track and said they’d seen a blue-green sports coat lying on a tree up near the falls, which are several kilometres away. They hadn’t seen Childe. The driver walked up the track and found the coat, and went on a little further to a place called Luchetti Lookout, which is no longer there. Here he found, on the other side of the safety fence, Childe’s hat, glasses and compass. It was time to call the police.

Senior Constable James Morey attended the scene. He found the items mentioned by the taxi driver, and noted that the compass was sighted on Pulpit Rock, a prominent landmark further around the valley. By the constable’s reckoning, to take a reading from the compass, Childe would have had to lie on the ground on the far side of the safety fence. There was no sign of Childe, or of anyone slipping over the edge, or of any other person. The drop was about 1,200 feet, with a ledge 200 feet up form the bottom.

Senior Constable Morey and others descended the cliff by the normal path, and inspected the area at the bottom, but they found nothing. They returned the next morning, and found Childe’s body on the ledge 200 feet up from the valley floor. The body was smashed up from the fall – one of Childe’s shoes, with part of his foot in it, was found only some months later. With difficulty the body was brought up to the top and taken to the local doctor’s surgery and then to Katoomba Hospital.

It was the policeman’s view that Childe had fallen over the cliff by accident. He was not wearing his spectacles and, according to some who knew him well, physically clumsy. His cousin had had lunch with him a week earlier and said Childe was healthy and financially secure, and had plans for future research, here and back in Europe. He stayed with archaeologists James and Eve Stewart near Bathurst, and Eve later recalled, “he was rejoicing in his retirement because he was free to devote all his time and energy to the things which interested him”.

A young historian who stayed with the Stewarts at the same time, and spent hours talking with Childe, later wrote, “I had the pleasure of knowing him at the time of his death and remember him as ebullient and full of enthusiasm. … he was particularly interested in the geology of the Blue Mountains, and I am convinced that it was this interest that brought him to his death. Though mentally alert he was physically somewhat tottery.”

The coroner found the Vere Gordon Childe had died by accident.

It was a logical conclusion, but in fact it was wrong. Vere Gordon Childe – who in London used to play bridge with Agatha Christie – had tricked everyone. Hints of this emerged in the coming years, although in some cases they’d been passed off at the time as jokes – Childe had an unusual sense of humour. For example, before leaving London he’d been asked by a friend what he’d do when he returned from Australia. According to the friend’s later account, “He replied that he doubted if he would return from Australia and that he would in all probability throw himself over some convenient cliff.”

Childe’s intellectual world was in chaos. A committed Marxist, he’d been shattered by the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956. His professional reputation as a prehistorian was under threat, with new methods and theories emerging to challenge those which had made his fame, and he’d retired early from his job at the Institute of Archaeology in London.

But such hints hardly confirmed that Childe had committed suicide.

The matter was resolved in 1980, when the Institute of Archaeology made an amazing revelation. Just before Childe died, he had sent its director a letter from the Carrington Hotel, along with a sealed envelope. He said the envelope contained matter “that may in time be of historical interest to the Institute” but asked that it not be opened until January 1968. For some reason, the Institute had hung onto it for another twelve years. It is one of the most extraordinary suicide notes every written – more like a polemic advocating voluntary, and even compulsory, euthanasia - and deserves to be quoted at length. Whether this bizarre document contains the real reasons Childe killed himself I leave to the reader to guess.

“The progress of medical science has burdened society with a horde of parasites – rentiers, pensioners and other retired persons whom society has to support and even nurse. They exploit the youth which is expected to produce for them and even to tend for them.

“I have always considered that a sane society would disembarrass itself of such parasites by offering euthanasia as a crowning honour or even imposing it in bad cases, but certainly not condemning them to misery and starvation by inflation.

“For myself I don’t believe I can make further useful contributions to prehistory. … although I have never felt in better health, I do get seriously ill absurdly easily; every little cold in the head turns to bronchitis unless I take elaborate precautions and I am just a burden on the community. I have never saved any money … On my pension I certainly could not maintain the standard without which life would seem to be intolerable … I have always intended to cease living before [I run out of money].

“The British prejudice against suicide is utterly irrational. To end his life deliberately is in fact something that distinguishes Homo sapiens from other animals even better than ceremonial burial of their dead. But I don’t intend to hurt my friends by flouting that prejudice. An accident may easily and naturally befall me on a mountain cliff. …

“I have enormously enjoyed revisiting all the haunts of my boyhood, above all the Blue Mountains. … Now I have seen the Australian spring; I have smelt the boronia, watched snakes and lizards, listened to the ‘locusts’. There is nothing more I want to do here; nothing I feel I ought and could do. I hate the prospect of the summer, but I hate still more the fogs and snows of a British winter. Life ends best when one is happy and strong.”